Does sign language sharpen your vision?

Image made on Canva

By now, most people are familiar with the idea that when you lose one sense, your other senses are heightened. Although losing one sense will not give you superpowers, your brain does adapt and change after sensory loss, often involving improved perceptual abilities in other domains. For example, D/deaf individuals – Deaf with an ‘uppercase D’ referring to people who identify as culturally Deaf and are engaged with the Deaf community, and deaf referring to the physical condition of having hearing loss – have been shown to exhibit enhanced visual sensitivity. For instance, D/deaf individuals seem to pay more attention, perform better, and react faster to movement in their periphery than those who are hearing. This perceptual difference is thought to be caused, in part, due to widespread changes and repurposing of the now underutilized auditory brain area.

However, these changes do not only occur in response to sensory loss. Rather, reorganization of the brain, otherwise known as neural plasticity, occurs for everyone throughout development and adult life, although typically on a much smaller scale. For instance, whenever we learn something new, connections within our brain are formed that help us access that information. In contrast, when we don’t use those connections often enough, they can be overwritten by information that is more relevant. For example, new connections would have formed when learning French in high school but never speaking it again would cause you to lose those connections.

In particular, the connections in D/deaf individuals’ brains are often adapted due to their acquisition of a visual-based language (i.e., sign language). As signed languages consist of intricate facial expressions and coordinated hand and body movements, connections associated with vision may be strengthened and allow for heightened sensitivity to visual information. However, there is very little information on how signed languages change the brain and its connections. Therefore, it is uncertain whether visual perceptual enhancements seen in D/deaf individuals stem from their use of a signed language, hearing loss, or both, as these often go hand in hand.

In an attempt to investigate the origin of these perceptual enhancements in D/deaf individuals, the current study uses bimodal bilinguals – individuals who know at least two languages in different modalities, in this case oral (English) and signed (American Sign Language (ASL)) – and hearing non-signers. The researchers aimed to assess whether ASL experience influences visual perception by focusing on two specific areas: human face perception and biological motion perception (i.e., the ability to recognize movement patterns made by living things, specifically humans).

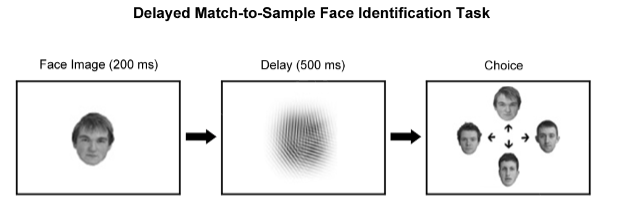

To do so, participants first performed a task where an image of a face was flashed onto a screen and after a short delay, they were shown 4 faces and asked to quickly and accurately identify which face matched with the one shown previously. This is called a delayed match-to-sample face identification task, and it allows the authors to measure the participants’ sensitivity to human faces. When the bimodal bilinguals and hearing non-signers performed this task, the researchers found no differences in accuracy between the groups and no differences when they compared ASL proficiency.

The participants then performed a task in which masked walkers (i.e., dots oriented in the shape of a person walking left or right) were presented at varying durations in their central or peripheral vision and asked to discriminate which direction they were moving. This direction discrimination task measures their sensitivity to human movements and, similar to the first task, there were no group performance differences between the bimodal bilinguals and the hearing non-signers. However, when the researchers looked at ASL proficiency, individuals who were more proficient were better able to tell direction when the masked walker was in the center of the screen and inverted. Further, bimodal bilinguals who learned ASL earlier in life had better performance for some of the longer duration walkers presented in the periphery.

By using these tasks and comparing group differences, the researchers would be able to determine whether acquiring a visual-based language would be enough to see visual enhancements. If indeed, the previously shown superior visual perception by D/deaf individuals is a result of only their sign language acquisition, the bimodal bilinguals should clearly outperform the hearing non-signers, and the magnitude of their advantages might be predicted by their individual sign language proficiency. However, in the current study, the researchers found that there were no differences in face-matching accuracy and direction discrimination performance between the two groups, suggesting that experience with sign language alone is not enough to account for the visual perceptual advantages seen in D/deaf individuals. However, while no overall group differences were found, the influence of ASL experience on performance for certain peripheral walking conditions, in the second task indicates that these perceptual enhancements may only occur in certain, specific conditions. Additionally, the lack of group differences may arise from the diversity in proficiency, age of acquisition, and sign language use among bimodal bilinguals.

Therefore, as one of the first studies to look at visual perception and ASL proficiency, the study highlights a need for further research to determine the effects of sign language acquisition on visual processing. Ultimately, these studies will help us understand how the brain adapts and what factors contribute to heightened sensory perception in those with sensory loss.

Original Article: Lammert, J. M., Levine, A. T., Koshkebaghi, D., & Butler, B. E. (2023). Sign language experience has little effect on face and biomotion perception in bimodal bilinguals. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 15328.