Two senses are better than one…but only if you’re older?

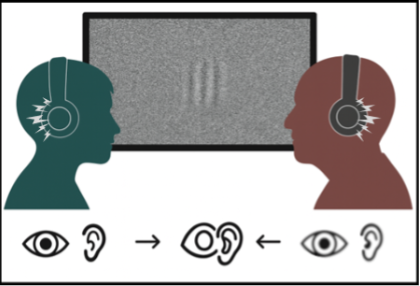

Figure 1. A visual representation of the methods for this study. On the left is a representation of a young individual and on the right is a representation of an older individual. Both are wearing headphones to hear the auditory stimuli while also visually observing a screen with a representation of the type of visual stimuli used in this study. This image is partially AI-generated using ChatGPT, Gemini and Canva.

Perhaps, you may recall the days of trying to understand and be understood by others behind face masks. Perhaps, you still experience a peculiar phenomenon when having a conversation with two people: one who is wearing a mask and one who is not. You may notice that being able to see the other person’s lips makes it easier to understand what they are saying. Does that mean we have an innate ability to lip-read? Well, not quite. Without accompanying vocal sounds, you likely would have a very hard time understanding what was said. It is said that seeing is believing, but both hearing and seeing are essential to understanding.

This ability to perceive the world around you more clearly with both auditory and visual information, compared to just auditory or just visual information, is called multisensory gain. Interestingly, multisensory gain appears to get stronger the older we get. Aside from attempts at lipreading entire conversations, as young adults, we manage just fine by filling in the gaps with only visual or only auditory cues. In these situations, combining both offers minimal improvements; however, as older adults we come out much further ahead by combining the two. For example, if we consider the loss of visual information when listening to masked speakers, previous research suggests that older adults are impacted more than younger adults when trying to understand speech during the COVID19 pandemic.

But why is this? Do we lose the ability to rely on a single sense? Or do we get better at combining two senses as we age? Which of these two explanations best explains the age-related improvements in multisensory gain we saw earlier? This was the question answered by the study published last year by Laura Schneeberger and a group from Dr. Ryan Stevenson’s lab at Western University in London, ON.

To investigate this, the authors took a simple sensory task and presented it to both younger (18-25 years) and older (55-80 years) adults. The task was straightforward: see if each participant can detect visual and auditory stimuli better when presented individually or combined. To do this, each participant watched a black and white static screen on a computer (Figure 1) and listened to noisy static through headphones. Then, throughout the 10-minute session, either a low, quiet tone would play under the noisy static, or a faint band of black and white bars would appear under the visual static of the computer screen (as pictured in Figure 1). These stimuli were randomly presented individually or at the same time throughout the session. When each participant detected either the sound, the black-and-white bars, or both, they pressed the space bar on the computer keyboard as fast as possible. Faster response times suggested faster perception.

The authors used two versions of this sensory response time task. In one version, the authors repeated previous research, keeping all the visual and auditory stimuli the same for all participants. This is the standard task where the difference in response times between the unisensory stimuli (audio or visual) and the multisensory stimuli (audio and visual) is often larger for older adults. As expected, the authors found the same difference between younger and older adults on this first version of the task.

In the second version of this task, the authors sought to explore why the difference is larger in older adults. To do this, they made a small change to this standard task: adjusting the strength of the audio and visual stimuli to match each person’s own perception. A separate group of younger (18-24 years) and older (55-80 years) adults completed this self-adjusted version of the task. Researchers first assessed everyone for the limits of their visual and auditory perceptions and then selected an individualized threshold for each participant. This threshold was the intensity where the individual could detect the stimuli 50% of the time. Thus, all stimuli were individually adjusted to match this 50% threshold.

This second version evaluated if the findings were related to changes in perception as we age. If older adults still displayed greater multisensory gain than younger adults, this would suggest the improvement in older adults is not related to declining vision and hearing. Rather, our ability to combine sensory information may improve with age. However, if the multisensory gain observed in the first task was related to differences in seeing and hearing abilities, then younger and older adults should show similar multisensory gain when the stimuli are matched to each individual’s abilities.

This was exactly what the study found: younger and older adults had the same levels of multisensory gain on this second task. This suggests that it is our visual and hearing abilities that play a key role not improvements in multisensory gain. In other words, our ability to combine sensory information does not improve with age. Certainly, when comparing sensory thresholds between the younger and older adults in this study, the older adults showed distinct age-related loss, especially in hearing. Taken together, as we experience age-related visual or hearing loss, we come to depend more strongly on multisensory gain to fill in the gaps.

The big takeaway from this study is that multisensory gain acts as a protective, built-in safety net for our perception. It helps to balance small age-related losses, shining at its strongest when we need it most. From the beginning, we have all the tools we need for multisensory processing. When we begin to experience age-related visual or hearing loss, we do not necessarily build new tools, but simply rely on pre-existing tools more often. The loss of visual information when listening to someone wearing a face mask becomes even more difficult for older adults due to the additional age-related loss of auditory information as well. Given that hearing loss was the most prevalent age-related loss in the current sample, it would be interesting for future research to explore if these tools work the same to balance out loss in both hearing and vision equally.

Original Article: Schneeberger, L. C., Lynn, A., Scarcelli, V., Seif, A., & Stevenson, R. A. (2024). Enhanced multisensory gain in older adults may be a by-product of inverse effectiveness: Evidence from a speeded response-time task. Psychology and Aging, 39(7), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000850